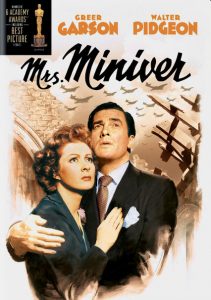

Mrs. Miniver-1942

Director William Wyler

Starring Greer Garson, Walter Pidgeon

Scott’s Review #841

Reviewed December 13, 2018

Grade: A-

Released in 1942 amid the horrific World War II, Mrs. Miniver (1942) was a smash hit, winning over audiences concerned with the troubled and uncertain times.

Decades later, the film does not age as well as other similarly themed films, but still entertains and tells a good story with an important theme.

The film is nestled in the war drama genre with romance. The film won numerous Oscars the year of its release, including Best Picture and star Greer Garson won for Best Actress.

The story is told from the perspective of an affluent British family and the struggles they face to keep things together during growing peril. The focus primarily remains on an unassuming housewife, Kay Miniver (Garson).

The supporting players do much to flesh out the film with fantastic performances by Walter Pidgeon, Teresa Wright, and Henry Travers as Clem Miniver, Carol Beldon, and Mr. Ballard, respectively.

The direction by William Wyler is astounding and adds to the perfectly crafted ambiance and homey details.

The family lives a comfortable life in a whimsical village outside of London. Quite idealized, they own a large garden and a motorboat on the River Thames.

Along with Kay and Clem, their three children of varying ages and their housekeeper and cook reside with them. Besides the parents, the central couple is son Vin (Richard Ney) and the prominent Carol (Wright); the pair initially disagree on politics but finally fall madly in love.

As the soap opera-style family situations continue, the war grows closer and closer to their house.

As Mrs. Miniver progresses, Vin enlists in the army to assist with war efforts, a German Nazi breaks into the Miniver house, a central character dies, and bombs and planes crash.

Through it all, Kay remains stoic and takes the family through challenging situations, adding melodrama to the film. The woman’s journey and resolve to keep everything and everyone intact is at the core.

The film is mainly a family drama with the Minivers and the townspeople experiencing trials and tribulations. In this way, Mrs. Miniver risks being a one-trick pony, albeit an emotional and teary-eyed one.

The film’s rich characteristics and polished nature make it more than it ought to be, and the superlative cast, production values, and timely release undoubtedly made it what it was in 1942.

In present times, however, Mrs. Miniver seems diminished in importance and relevance with a sappy and overly sentimental feel, World War II in the distant past, and several other wars come and gone.

Wyler carefully packaged the film to hit every emotion, from the bombastic musical score to the proper English characters to the comic relief housekeeper.

The film is a giant Hollywood production, but perhaps a bit too perfect to age with any zest or reason to watch more than once.

The film might be better remembered for its strong female lead. Told from Kay’s perspective, it was unusual in 1942 for a movie (especially with a war theme) not to have the story from the male point of view. Still refreshing in 2018, this quality was downright groundbreaking at the time.

Kay stays strong and proud through the ravages of war that are closing in on her family with unbridled boldness and nary a simpering quality. Wright’s Carol is an early champion for strong, female-driven characters, and, in a more minor way, she is also a muscled female role model.

Mrs. Miniver (1942) is a well-crafted film of its time that displays lavish production values and strong characters worthy of admiration.

The film is a significant win for a glimpse of the 1940s, especially for fans of good, solid drama. There are no significant flaws to harp on, but the overall piece has not aged exceptionally well, and other similar films (Casablanca, 1942) are more memorable.

Oscar Nominations: 6 wins-Outstanding Motion Picture (won), Best Director-William Wyler (won), Best Actor-Walter Pidgeon, Best Actress-Greer Garson (won), Best Supporting Actor-Henry Travers, Best Supporting Actress-Teresa Wright (won), Dame May Whitty, Best Screenplay (won), Best Sound Recording, Best Cinematography, Black-and-White (won), Best Film Editing, Best Special Effects