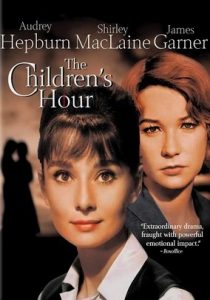

The Children’s Hour-1961

Director William Wyler

Starring Audrey Hepburn, Shirley MacLaine, James Garner

Scott’s Review #620

Reviewed March 3, 2017

Grade: B+

The Children’s Hour (1961) is one of the earliest films to center around an LGBTQ+ theme and the subsequent scandals the subject would provoke in the innocent year of 1961-pre Civil Rights and pre-Sexual Revolution.

However, since the film was made in the year that it was, homosexuality was presented as something dark and evil rather than something to be accepted or even embraced.

Still, the film and its director, William Wyler, are brave enough to recognize the topic. Still, they cannot create a compelling film rich with well-written characters and some soap opera-style drama.

The Children’s Hour is based on a play from 1934 and written by Lillian Hellman.

The setting appears to be New England, perhaps Connecticut or Massachusetts, though the film never identifies the exact area.

College friends Karen (Audrey Hepburn) and Martha (Shirley MacLaine) open a private all-girls boarding school catering to their affluent community. They run the school with Martha’s Aunt Lilly, a faded Broadway actress who often hen-pecks the women.

Karen has been dating handsome obstetrician Joe (James Garner) for two years. When he proposes marriage, she hesitantly accepts, which saddens Martha.

All the while, spoiled brat child Mary, furious over being punished by her teachers, plots revenge against Martha and Karen and embellishes a heated discussion between the ladies into a scandalous lie she whispers to her grandmother (Fay Bainter).

The grandmother promptly tells the parents of the other students, who remove their children from the school en masse. The lie is that Karen and Martha are lovers, and Mary witnessed the two women kissing.

Meanwhile, Mary is blackmailing a fellow student, Rosalie (Veronica Cartwright), over a stolen bracelet.

The town ostracizes Martha and Karen.

The Children’s Hour becomes even more compelling when one of the women begins to realize that she does indeed have homosexual feelings towards the other woman and has always harbored anger and resentment as well as feeling “different” from other women.

As well-written as the film is, the fact that the audience does not get to hear what Mary whispers to her grandmother is instead telling and prevents the film from being even more powerful than it is.

Also, the downbeat conclusion to the film sends a clear message that in 1961, audiences were not ready to accept lesbianism as anything to be normalized or to be proud of.

The decision was made to make it abundantly clear that one of the central characters is not a lesbian. Any uncertainty may have risked freaking out mainstream audiences at the time.

Since the traditional opposite-sex romance between Karen and Joe is at the forefront of the film, I did not witness much chemistry between actors Hepburn and Garner. Still, I might have been at the point of achieving a subliminal sexual complexity.

The Children’s Hour and William Wyler deserve heaps of praise for going so far as to suggest that censorship in film in 1961 would allow them to offer nuggets of progressivism mixed into a brave film.

Incidentally, Wyler made another version of this film in 1936 named These Three. Because of the Hays Code, any hint of lesbianism was forbidden, causing Wyler to create a standard story of a love triangle between the three, with both Martha and Karen pining after Joe.

What a difference a couple of decades make!

MacLaine and Hepburn must be credited with carrying the film and eliciting nice chemistry between the women. However, it is too subtle to be realized if the chemistry is of a friendship level or a sexual nature.

And I adore how Wyler makes both characters rather glamorous and avoids stereotypical characteristics.

Oscar Nominations: Best Supporting Actress-Fay Bainter, Best Sound, Best Art Direction, Black-and-White, Best Cinematography, Black-and-White, Best Costume Design, Black-and-White