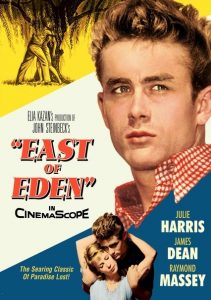

East of Eden-1955

Director Elia Kazan

Starring James Dean, Julie Harris, Jo Van Fleet

Top 250 Films #205

Scott’s Review #1,092

Reviewed December 17, 2020

Grade: A

James Dean wasn’t with us for very long, tragically dying at the tender age of twenty-four, but he made three films: Rebel Without a Cause (1955), Giant (1956), and East of Eden (1955), all-powerful showcases and unique.

Dean gives a brilliant, humanistic, and sometimes tragic performance.

East of Eden, his first film, is the only one he got to preview. I hope he liked it because it will live forever as a gem.

Based on the John Steinbeck novel of the same name, the story is also a biblical retelling of Cain and Abel, brothers who clash and spar. Director Elia Kazan, famous for supporting and using Method actors in his films, gave a tremendous performance as Dean, which was key to the film’s empathetic nature.

The key to East of Eden is that it reflects on several characters, who are both good and bad, possessing qualities of both, detailing their struggles.

Nobody is completely good or completely bad. The story analyzes good versus evil and the multitude of layers between both extremes, making the experience juicy, truthful, and brilliant.

Set in 1917, during World War I, two sunny coastal California towns are the backdrop for the action. Cal Trask (Dean) perceives his father, farmer Adam (Raymond Massey), as favoring Cal’s brother, Aron (Richard Davalos). This leads to much resentment, jealousy, and conflict. Aron is the apple of Adam’s eye, and we wonder why.

Furthering the drama is Cal’s love for Aron’s girlfriend, Abra (Julie Harris), who doesn’t rebuff any advances. Cal and Aron’s mother, Kate (Jo Van Fleet), who they think is dead, is alive and well and running a brothel in a nearby town. Assuming a different name, she harbors secrets.

Before you get the impression this is some cheesy soap opera, East of Eden, like the novel, is heavily character-driven and nuanced with development. It ultimately draws the audience in and envelops everyone in its simmering qualities.

East of Eden is packed with powerful scenes after powerful scenes, and in more than one, the allegiances and rooting values shift from character to character.

Some of the best moments are when Cal self-destructs after his father refuses his birthday gift, or when Cal cruelly reveals the true nature of their mother’s profession to the innocent and unsuspecting Aron.

Finally, Cal and Abra’s kiss atop a Ferris wheel is filled with smoldering desire and deadly consequences.

The acting was tremendous across the board. Much of the credit must go to Kazan for pulling fabulous performances out of the players, a talent only a Method acting director can achieve.

While the cast is exceptional, the film belongs to Dean, who provides enough emotion and vulnerability to sustain his character’s topsy-turvy, tortured existence. Knowing that the actor died soon after filming gives the film an eerie and sentimental feel.

This is comparable to a more modern-day example when Heath Ledger died after giving a brilliant performance in The Dark Knight (2008).

This is hardly a war film or a guy’s film, as the ladies also get to shine with rich characters. Julie Harris and Jo Van Fleet portray flawed characters in juicy roles rife with meaty scenes filled with conflict.

As with most of Steinbeck’s works, specifically The Grapes of Wrath, the landscape is a character, and East of Eden is no exception. With dusty roads and mountainous backgrounds, events ooze with atmosphere and beauty.

The lush northern coastal California landscape portrays a grandiose magnificence that counterbalances the conflict its inhabitants are experiencing.

The central note to take away from East of Eden (1955) is that we are complex creatures with a mixture of good and evil. We sometimes want to do the right thing, but in doing so, we hurt those we love. The main characters suffer from pain, regret, good intentions, poor decisions, and loss.

The rich dialogue, adaptation, acting, and cinematography make the film near perfection.

Oscar Nominations: 1 win-Best Director-Elia Kazan, Best Actor-James Dean, Best Supporting Actress-Jo Van Fleet (won), Best Screenplay