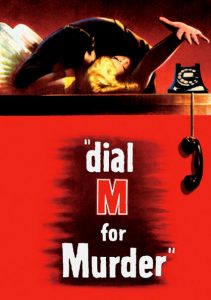

Dial M for Murder-1954

Director Alfred Hitchcock

Starring Ray Milland, Grace Kelly

Top 250 Films #120

Scott’s Review #995

Reviewed February 28, 2020

Grade: A

A fabulous offering by stylistic director Alfred Hitchcock, Dial M for Murder (1954) arrived on the scene when the cinematic genius was at the height of his success in the United States, following his success in England.

The late 1950s and early 1960s revealed his best offerings, but this is no slouch. The film mixes thrills, double-crosses, and murder in a way only Hitchcock can —perfectly.

It is fast-paced and shot almost like a play, using primarily one set. It is based on the Broadway hit, which came first.

An English former tennis champion, Tony Wendice (Ray Milland), hatches a scheme to kill his wealthy but unfaithful wife, Margot (Grace Kelly), who’s embroiled in a liaison with handsome writer Mark Halliday (Robert Cummings).

When Tony’s plans go awry, he attempts the second act of deceit, but events spin out of control when Margot, Mark, and a sly Scotland Yard inspector (John Williams) begin putting the pieces together.

The film is popular because of its conventional, pure Hitchcock story. The viewer immediately knows who the killer is and his motivations—his hunger for wealth and jealousy of another man.

The most fun is when hiccups begin to form, and Tony must fly by the seat of his pants to cover his tracks and think of another way to seal Margot’s fate. If he cannot murder her, why can’t he send her to prison?

Milland is perfect in the role with eye shifts and head turns.

Set pieces, such as a key and a handbag, add zest to the film. The plot gets juicier and juicier when it is revealed that there are multiple keys. The flat where Tony and Margot reside is beautifully designed with state-of-the-art furniture and decorations, making the set a character.

Lavish curtains and French doors are utilized during the late-night attempted murder scene, which is thrilling to witness, leaving the viewer with heart palpitations.

The brilliance is that the viewer does not intend to hate Tony, at least not this viewer. While he is not likable, his motivations can be somewhat understood. Conversely, Margot and Mark are not heroes; their shenanigans come back to haunt them.

I dare say that Grace Kelly has had better roles in Hitchcock films. To Catch a Thief (1955) immediately comes to mind. Margot is not a particularly strong character and is relatively weak.

Dial M for Murder has commonalities with two other Hitchcock gems. As with Strangers on a Train (1951), a tennis star is utilized as a significant character, and twisted strangulation is the game. Also, a tit-for-tat technique is used.

Like the underappreciated Rope (1948), the one-take sequence style and the film’s potential as a stage play are noticeable traits. Those films are good ones to be in the same company with.

The final thirty minutes pass at breakneck speed as we wonder what will happen next. The cat-and-mouse activities are delightful and remind us that the film is essential and stripped down compared to his later films.

One set, good actors, and a full-throttle story do wonders to satisfy a fan. The camera movements and techniques are key to the entire film, as a shot here or there is timed with flawless precision. Hitchcock used 3-D filming, which was inventive for the time.

Although perhaps not as famous as Hitchcock’s delights like Psycho (1960), Vertigo (1958), or North by Northwest (1959), Dial M for Murder (1954) serves as much more than a warm-up act for those classics.

This film is one to remember with a fast pace, twists and turns, and good British sensibilities. Its setting is a stylish London flat, and the sophistication is suitable.