Bon Voyage! -1962

Director James Neilsen

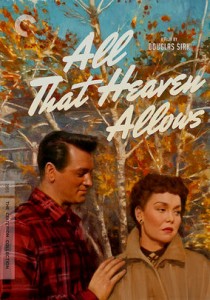

Starring Fred MacMurray, Jane Wyman

Scott’s Film Review #1,508

Reviewed January 8, 2026

Grade: B

James Neilson, known for directing both film and television and well-versed in the Walt Disney vibe, having worked throughout the 1960s on the television series Walt Disney’s Wonderful World of Color, provides fans of European travel with a feast of locale riches.

He offers Bon Voyage! (1962), an entertaining family adventure that multi-generations can enjoy.

Paris is the primary setting with the Eeifel Tower, the Louvre Museum, and Notre Dame prominently featured. Still, London, the French Riviera, and snippets of New York City are also featured.

Watching the film decades after 1962 is a pure delight, seeing how outfits, people, and landmarks have changed over the years.

This is the obvious highlight for me, though the dynamic between the Willards is fun in a lighthearted way, seesawing between comedy and sentimentality.

At times, the comedy is more bafoonish than laugh-out-loud, and the sequences more plot-driven than believable.

Nonetheless, the chemistry between the actors is prominent, and the story is wholesome and predictable, culminating in a feel-good experience.

After twenty years of marriage, Terre Haute, Indiana, plumber Harry Willard (Fred MacMurray) finally makes good on his promise to take his wife, Katie, played by Jane Wyman (ex-wife of United States President Ronald Reagan), on a luxurious cruise to Europe.

Hardly a honeymoon; they are accompanied by their brood: nineteen-year-old son, Elliott (Tommy Kirk), eighteen-year-old daughter, Amy (Deborah Walley), and eleven-year-old son, Skipper (Kevin Corcoran).

From the moment the group arrives at the dock by taxi cab, the bumbling Harry nearly loses the passports, and an unending series of mishaps ensues, including Amy’s romantic entanglement with handsome, wealthy Nick (Michael Callan), a sewer adventure, and a passionate Hungarian man pursuing Katie.

The film experiences highs and lows throughout.

Is Nick meant to be a disliked character? He’s actually my favorite character, except maybe for Harry, and is written quite daringly for the early 1960s, with him fervently questioning marriage and other institutions.

He ultimately disregards his wealth and decides to relocate to New York to forge a career without his family’s wealth or expectations, much to his mother, the contessa’s (Jessie Royce Landis), chagrin.

However, I could have done with more than one scene from the fabulous Landis, best known for Hitchcock’s To Catch a Thief (1955) and North by Northwest (1959), in which she also plays interesting mothers.

Though she steals her lone scene as she drips with jewels, a gorgeous dress, and struts around her lavish party, exclaiming ‘dahling’ whenever she can, we never get enough of her fabulous antics.

Still, Nick seems to be the only character with a solid set of balls who stands against societal expectations. His tense scenes with Harry about life and love are the only times the film’s writing is daring.

The rest of the writing is relatively safe and tepid.

Amy comes across as a bit wishy-washy about sex and marriage, and after prancing along the beach in a tacky outfit, she seems more of a nitwit than a serious character.

Maybe she and Nick don’t belong together after all?

Elliott, while cute in his pursuit of young women and attempts to impress them with unfounded wealth, his act grows tiresome by the film’s conclusion.

The most palpable couple is Harry and Katie, whose tender love shines through as an inspiration to other characters. The chemistry between MacMurray and Wyman is strong, showcasing them as reliable and stalwarts of true love.

Bon Voyage! (1962) is a kindhearted film, marginally recommended mainly for the locales. It’s mostly a safe affair, save for one character, and pales in comparison to more weighty films to come during the 1960s.

Oscar Nominations: Best Costume Design (Color), Best Sound