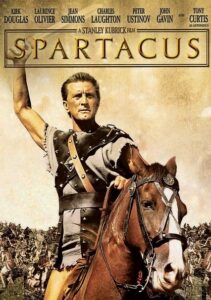

Spartacus-1960

Director Stanley Kubrick

Starring Kirk Douglas, Laurence Olivier, Jean Simmons

Top 250 Films #247

Scott’s Review #1,250

Reviewed April 30, 2022

Grade: A

Typically, when influential director Stanley Kubrick’s name is uttered, films such as The Shining (1980), 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), and Barry Lyndon (1975) are immediately thought of, and for obvious reasons.

The haunting, moody musical score, the long camera shots, the dark humor, and the clever camera tricks are easy to pinpoint.

1960, the director was hired to direct the gorgeous epic Spartacus after Hollywood star Kirk Russell unceremoniously fired the first director.

None of the previously mentioned elements are easy for me to notice and are more or less absent, but a grand battle scene in a luscious green field is very reminiscent of Barry Lyndon. This is likely because Spartacus was not Kubrick’s film entirely; instead, it belonged to others with more clout.

Spartacus is a brilliant film for many reasons. Some epics suffer from a hokey, cliched feel and can be overwrought, predictable, and tired.

The rebellious Thracian Spartacus (Russell), born and raised a slave, is sold to Gladiator trainer Batiatus (Ustinov). After training to kill for the arena, Spartacus turns on his owners and leads the other slaves in rebellion.

As the rebels move from town to town, their numbers increase as escaped slaves join their ranks. Under the leadership of Spartacus, they make their way to southern Italy, where they intend to cross the sea and return to their homes.

Spartacus is grand, sweeping, cinematically significant, and everything else you’d expect from a 1960s Hollywood epic with enormous stars of its day. Looking beneath the surface, the film is riddled with interesting tidbits like bisexuality, homoeroticism, and violence, more in tune with an art film or modern war film than the safety of a movie made during this time.

Particularly noteworthy is that Dalton Trumbo wrote the screenplay. One of the Hollywood Ten, he refused to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1947 during the committee’s investigation of alleged Communist influences in the motion picture industry.

After the release of Spartacus, it marked the beginning of the end of the Hollywood Blacklist for Trumbo and other affected screenwriters.

Thank goodness.

In a famous scene, recaptured slaves are asked to identify Spartacus in exchange for leniency; instead, each slave proclaims himself to be Spartacus, thus sharing his fate.

The suggestion is that this scene was meant to dramatize the solidarity of those accused of being Communist sympathizers during the McCarthy era.

Besides the political importance, Spartacus showcases a beautiful romance between Spartacus (Russell) and Varinia (Jean Simmons), a gorgeous slave girl. The tenderness and authenticity are palpable as many of their early scenes involve no dialogue but only longing and expression through both actors’ eyes.

I celebrated the connection between the actors at the forefront of much romance. Russell carries the film with calm masculinity, quickly making him heroic and likable.

He is the charismatic, good guy who has been wronged and ill-fated.

A sequence oozing with machismo and homoeroticism occurs when evil Crassus (Olivier) is bathed by his slave boy Antoninus (Tony Curtis). He seductively explains that while sometimes he prefers snails, he also likes oysters. The implication is that he is bisexual, brazenly so, and expects the youngster to become his sex slave.

The warmth of the bathtub and the luxurious atmosphere contrast with the proximity and touch of both male characters.

In 1960, this scene was way ahead of its time.

The conclusion of Spartacus is melancholy and surprising. Having bested Rome’s cruelty, one might have expected to see Spartacus and Varinia happily ride off into the sunset.

This doesn’t happen, and the film is more affluent in it. There is pain and despair as there were in real life. Wisely sparing complete doom and gloom, the ending is satisfying as one central character escapes a deadly demise and conjures ahead.

Spartacus (1960) is one of the greats. It has muscle and texture, and many below-the-surface nuances are ripe for discussion. For these reasons, it’s a must-see.

Oscar Nominations: 4 wins-Best Supporting Actor-Peter Ustinov (won), Best Art Direction-Color (won), Best Cinematography-Color (won), Best Costume Design-Color (won), Best Film Editing, Best Music Score of a Dramatic or Comedy Picture