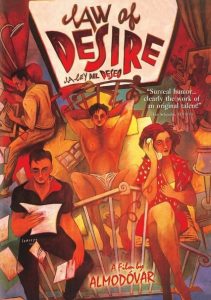

Law of Desire-1987

Director Pedro Almodovar

Starring Antonio Banderas, Eusebio Poncela, Carmen Maura

Scott’s Review #1,021

Reviewed May 8, 2020

Grade: B+

Law of Desire or La ley del Deseo (as translated in original Spanish) is a 1987 film written and directed by Pedro Almodóvar.

Quite groundbreaking for its time and penned by a respected director, the film was rich in offering what was rarely presented in films during the 1980s- a complex love triangle between two men and a trans woman.

The fact that the trans woman is the sister of one of the men is a bonus to the buttery soap opera premise.

In 2020, when LGBTQ+ films are more plentiful in cinema (at least at the indie level), Law of Desire suffers slightly from a dated feel and parts drag along. It’s tough to heavily criticize a piece so brazen as this one was when it was released to art-house theaters and musty metropolitan theaters.

As groundbreaking as the film must be given credit for, the story now feels sillier than it should, and more outlandish than it probably intended to be over thirty years ago.

The fabulous setting of Madrid, Spain is the backdrop for the luscious tale of love, obsession, jealousy, and revenge, think the prime-time television series Dynasty on steroids.

Cocky Pablo (Eusebio Poncela), a successful gay film director with his pick from a bevy of young, good-looking gay males, is madly in love with Juan (Miguel Molina), though he has a roving eye.

Suave Antonio (Antonio Banderas), who comes from a conservative family, is new to the gay scene and falls madly in love with Pablo when Juan goes to find himself. Tina (Carmen Maura), who likes men and women, has just been dumped and is vulnerable.

Besides the obvious daring gender-bending, this story could be a simple one told many times across many genres. Almodóvar spins things into a frenzy as the plot unfolds adding manipulations, sub-plots, and bizarre characters into the mix.

For example, Ada is Tina’s surrogate daughter and is a precocious ten-year-old girl in love with Pablo. Ada refuses to go back with her mother (Bibi Andersen) when she comes back to whisk her off to Milan to meet a man she just met.

The gay subtext is what is center stage here. Back in the 1980s, the term LGBTQ+ was on nobody’s radar, and having any representation at all in cinema was still territory barely scratching the surface.

This point kept returning to me throughout the film and I imagined how fresh the experience would have been to any gay man or gay woman fortunate enough to have seen it. I am not sure any of the characters would serve as great role models, but the representation is nice.

Almodóvar adds in a good deal of naked flesh for an added treat.

Several comic scenes arise with gusto. Antonio, who lives at home with a religious zealot of a mother, convinces Pablo to sign his letters from “Laura P”, a character from his latest play, to trick Antonio’s nosy mama.

Tina, not much of an actress, is cast in Pablo’s one-woman theatrical productions. She thinks her performance is great, but Pablo thinks she stinks. The comical moments are the ones that work best, giving the plentiful offbeat characters a chance to let loose and shine.

Towards the conclusion, Law of Desire takes a tragic and Shakespearean turn. A drunken Juan is thrown off a cliff to his death prompting an investigation with Antonio and Pablo both prime suspects.

Finally, a kidnapping and police stand-off ensues with a murder/suicide providing the film’s final moments.

I am not a fan of the title that Almodóvar chooses. Preferably would be a title that is a bit more titillating. Even Lust of Desire or Object of My Desire would have been better choices. Law of Desire screams of a tepid episode of television’s Law & Order.

For a director with such an outlandish approach and such bizarre characters, the title is bland, banal, and tough to remember.

Those seeking a kinky and provocative late-night affair will find Law of Desire (1987) a good old time. It lacks much of a clear message instead providing a sexy romp and dreary ending.

Running the gamut of adding musical score pieces as unique as the 1970s The Conformist, a film also shrouded in same-sex desire, to cheesy 1980s synth-laden beats, adds some confusion.

Nonetheless, diversity and inclusiveness are good recipes to chow down on and celebrate.