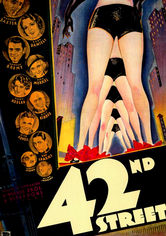

42nd Street-1933

Director Lloyd Bacon

Starring Warner Baxter, Ruby Keeler, Bebe Daniels

Scott’s Review #1,281

Reviewed July 28, 2022

Grade: A-

Whenever I watch a film made in the 1930s, I am reminded of cinema’s vastness and blossoming.

Filmmakers could do unique things back then, having very little of what filmmakers have in the modern day for technology’s sake.

I’ve heard it said that films of the 1930s are dated and dusty, the acting style is different, and the musical scores always have a standard sound. I find them like little presents beckoning to be opened to escape to another time, long ago.

The famous musical 42nd Street (1933) has been a Broadway stalwart since its debut. However, this is a falsehood since a stage adaptation of the film debuted on Broadway in 1980, winning two Tony Awards, including Best Musical.

Director Lloyd Bacon creates a slow and steady build to set the drama properly. The final thirty-five or forty minutes culminate in a lavish and fascinating extravaganza of the gala show opening.

All in all, events transpire in a brisk one hour and twenty-nine minutes. If I’m honest, I could have done with another ten minutes of the merriment-laden conclusion.

I giggled with delight at the professionalism inhabiting unique cinematography sequences like a camera rolling through a dozen spread legs to land on a handsome young couple’s face.

The Great Depression Era is the focus in a timely fashion, and props go to all involved for emphasizing this dastardly time with an escapist show.

Revered and impatient Broadway director Julian Marsh (Warner Baxter) has fallen on hard times like the rest of the United States. His doctor warns him to care for his health, but his finances are dire.

He launches an ambitious musical as a final production before his retirement. The lead actress, bitchy Dorothy Brock (Bebe Daniels), is torn between two men, the show’s rich financer, Abner Dillon (Guy Kibbee), and struggling actor Pat Denning (George Brent).

Meanwhile, aspiring young performer Peggy Sawyer (Ruby Keeler) hopes for her big break. She is entirely green and impressionable but humorously looks similar to Dorothy, right down to their curled hairstyle.

It’s easy to see what direction the plot is going in, but instead of an All About Eve (1950) theater story of one actress scheming for the role of another actress, events happen organically.

The first portion of 42nd Street is all well and good. We get snippets of the women traversing amongst their male admirers, and Julian becomes increasingly frustrated with the incompetent talent, but I keep hoping events will finally take off.

The romantic triangles and irritated threats to fire the cast almost get repetitive until the spectacular second act.

When the company is reduced to the opening in Philadelphia, the dregs of society to them, instead of the bright lights of New York City, 42nd Street becomes a different type of film.

A magical and marvelous escapade of leggy performances, astounding costumes, and song and dance numbers emerges onto the big screen before my delighted eyes. It is startlingly like watching the production in real time.

The cherry on top was watching the petrified Peggy fill in for the injured Dorothy. Instead of the women continuing their feud, the older Dorothy gives Peggy a pep talk about how much the crowd wants to like her, and she has no reason to be nervous.

She’s got it, and Dorothy’s got her back.

The moment is filled with sweetness as the veteran passes the baton to the upstart. Dorothy’s words resonated with me as any entertainer, public speaker, or anyone else can take her advice to heart.

The musical numbers are cheery and robust, led by the toe-thumping title track, which I continue to hum along to while writing this review.

A gripe is that, according to legend, Julian is a gay character, but there is never a moment where the film implies this. A pleasant jolt would have been for him to at least flirt with a cast member.

Old-fashioned has rarely felt better because 42nd Street (1933) provides enough flash, dance, and razzle-dazzle to make its audience harken back to the good old days of classic cinema.

There are even some words of wisdom to embrace.

Oscar Nominations: Best Picture, Best Sound